By Matt Kelly

Lack of access to fruits and vegetables is directly related to higher rates of illnesses in many of our communities. But what if we removed the problem of access as a contributor to these health inequities in our region? Can we use our region’s agricultural abundance to ensure access to healthy food for all residents?

This article is part of an on-going series that explores these questions.

"It really has been a good year for gardening."

Michelle Weiler steps up in front of the class. She is a nutritionist with the Monroe County Cornell Cooperative Extension and an educator for the Finger Lakes Eat Smart NY Program. About 20 people are gathered in the simple, bare community room at Pinnacle Apartments in Rochester. The complex provides assisted, affordable living to hundreds of people of different ages and with a wide range of backgrounds, including special needs or a history of addiction. Around half the people who live here are elderly; all are low income. An interpreter is quietly echoing in Spanish everything Weiler says for a group gathered around one table.

"It's been a great year for eggplants, peppers, garlic, root vegetables," she continues, getting everyone's attention with casual conversation before starting into the actual lesson. "You know, every season the garden grows, you have some good things and you have some things that aren’t so successful."

Out behind Pinnacle’s concrete tower, hidden away from the traffic and noise of South Clinton Avenue, is a large community garden. This productive green space has been here since before PathStone took ownership of the building in 2013. It was started by residents who were interested in growing their own food, with the support of management.

Today it's still maintained by the people who live at Pinnacle, with support from the Eat Smart NY Program. The program's garden team does the literal groundwork of tilling the soil, providing the seeds and starter plants, and coordinating the harvest. The produce is then made available to the residents of Pinnacle. This year the patchwork of plots is filled with tomatoes, peppers, squash, beans, radishes, lettuce and herbs.

"So, I want to do a class today because right now it’s time for harvesting herbs," she says. "And I want to talk about a couple of things."

First is the amount of sodium in what the residents regularly eat. Weiler explains that salt is found in almost everything we consume, but it’s particularly high in processed foods. And a regular diet that is high in sodium can lead to high blood pressure, heart disease and heart failure. Second, however, is the challenge of reducing the sodium in a person's diet.

"The minute you take away salt, your food tastes bland, right?" There are nods of agreement all around the class. "So herbs are a great way to incorporate flavor into your food. And you can get them right from the garden. You just pick them and have them."

Herbs are neither fruit nor vegetable, and they are by no means the basis for a meal. But they are easy to grow and have the power to transform what might otherwise be bland fare into wonderfully delicious meals.

Weiler hands out a paper to class that lists some basic facts about the salt in our foods. She holds up a copy and points out that five percent of the sodium in the typical American diet is added during cooking. Six percent is added at table. Twelve percent occurs naturally in the food we eat. But an overwhelming 77 percent comes from processed foods.

"That’s really, really high," Weiler says. She pauses and turns to the table behind her, which has different types of food arranged on it. She holds up one for the class. "This is a good example."

With nods and murmured acknowledgement, it's clear that everyone recognizes the small rectangular block wrapped in orange and white plastic.

"How many of you love Ramen noodles?" she asks, smiling back at the group. The nutritional label says there are 830 milligrams of sodium in just one a serving – half the packet.

"Anyone know what your daily amount of sodium should be?"

It’s less than 2,300 milligrams for healthy adults.

"I don’t want to deprive you of your Ramen noodles," she says. These noodles are very cheap and they can feed a family. "But how could we change this to have less sodium?"

Someone in the class shouts an answer: Don’t use the seasoning packet. Michelle smiles and nods.

She says that anything we find in a can or on a shelf is typically going to contain a lot of sodium. The more foods get processed, the more sugar, fat and sodium they are likely to have. Which is why sticking to fresh foods is so important, because you have much more control over these three ingredients.

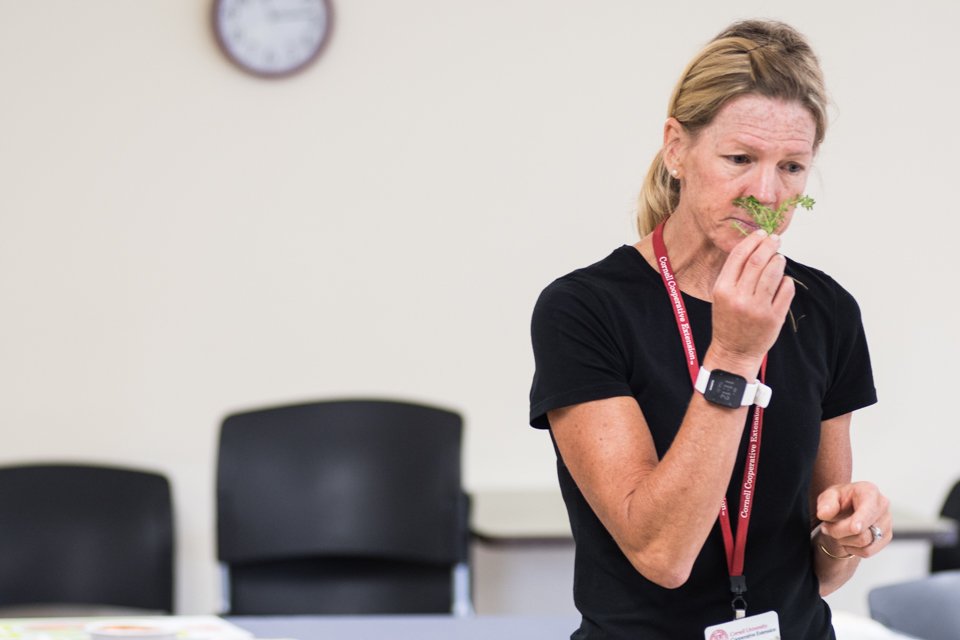

"I love cooking with fresh herbs," Weiler says, pulling several leafy bunches out of a bag. One by one, she passes them around the class to smell and discuss. Each time, she brings the bunch to her nose before passing it on.

Everyone takes a moment to crush the different herbs between their fingers and smell the lingering aromas. They try to guess the name of each herb, and then discuss how to use it in the kitchen. There is cilantro for Mexican dishes. Basil for Italian cuisine and tomato-cucumber salad. Thyme for chicken or steak. Sage for Thanksgiving stuffing. Lemon balm for lemon-pepper chicken or tea. Even lavender, which makes a great tea as well.

"These are fresh, I just picked them this morning," she says. "But you can go to the public market and use your EBT card to buy herbs. That’s a good way to start introducing herbs into your pantry and replacing the sodium."

Someone asks a question: You can’t buy herb plants with food stamps, can you? Does SNAP (the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) allow you to buy potted plants?

"Yes, you can," says Weiler.

According to the SNAP website, individuals and families can use their benefits to buy plants which produce food for the household to eat. But even more than that: people can use their benefits to buy seeds. This opens up the possibility for individuals and families to grow precisely the fresh foods and herbs that Weiler is talking about.

Herbs, in particular, don't need much space at all to grow. They can be planted in pots on a balcony or porch, or in a window box. They can be brought inside and grown throughout the winter, with the right amount of light.

Weiler isn’t sure how many of the people she works with actually use their SNAP benefits to purchase seeds and plants for growing their own fresh foods. However, she does know that having fresh herbs right at your fingertips makes it much easier to replace salt with a healthy alternative.

Plus, there are the less tangible benefits. “I have seen participants watch their own gardens grow,” she says. “It gives them an activity to tend to on a daily basis as well as seeing the rewards of healthier eating.”

--

We’d like to thank Michelle Weiler and the Eat Smart NY team for all the important work they do, and for their help with this story.